Editor's Note: On May 2, 1882, Charles Stewart Parnell was released from Kilmainham jail in Dublin after agreeing to the so-called 'Kilmainham Treaty,' in which he urged his supporters to avoid violence while boycotting. Below, IrishCentral founder Niall O'Dowd explores how Parnell was a victim of 'fake news' in 1887.

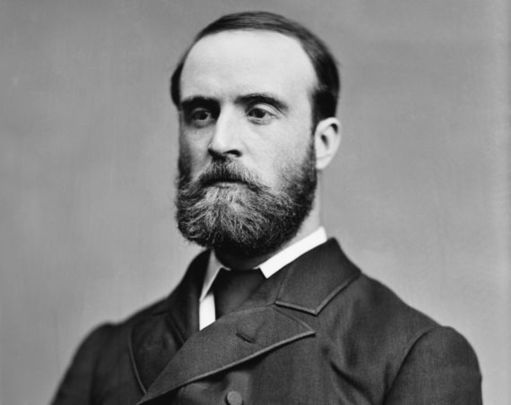

Charles Stewart Parnell was an Irish nationalist politician and one of the most powerful figures in the British House of Commons in the 1880s.

Fake news is nothing new. British enemies of Charles Stewart Parnell (June 27, 1846 - October 6, 1891) used it to try to bring down the Irish Home Rule leader – and almost succeeded – back in the 1880s.

On May 6, 1882, two leading members of the British government in Ireland, Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish and the Permanent Under-Secretary for Ireland T.H. Burke, were stabbed to death in Dublin’s Phoenix Park by the Irish National Invincibles, a radical nationalist group.

Five years later, at the height of Parnell’s powers and with Home Rule for Ireland looming in March 1887, The London Times published a fake newsletter which they had paid $2,000, $200,000 by today’s currency, which bore Parnell's signature and condoned the murder of T.H. Burke in a specific language.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The letter was supposedly written by Parnell to Patrick Egan, a Fenian activist, and included the line, "Though I regret the accident of Lord F. Cavendish's death I cannot refuse to admit that Burke got no more than his deserts" and was signed "Yours very truly, Charles S. Parnell."

On the day it was published (April 18, 1887), Parnell described the letter in the House of Commons as "a villainous and barefaced forgery.”

Nonetheless, the impact was immediate and calls for Parnell's resignation and prosecution for inciting violence came loud and strong.

The Parliament eventually appointed a special three-judge committee to hear the evidence, and later asked for the appointment of a select committee to inquire whether the facsimile letter was a forgery.The government refused this request but appointed a special committee composed of three judges, to investigate all the charges made by the Times.

Parnell suspected that fellow Irishman Richard Pigott, a Meath native once a supporter, now a sworn enemy and working for the crown, was responsible for giving the letters to the Times. But he had to prove it as Pigott told a different tale.

Pigott’s evidence was that he had been employed by the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union to find documents that might incriminate Parnell in defending the Phoenix Park murders, and he had bought the facsimile letter, with other letters, in Paris from an agent of Irish radical group Clan na Gael. However, he said he had no knowledge of how they ended up in the Times once he had passed them on.

Parnell had to destroy Pigott's testimony.Luckily he hired an extraordinary lawyer, sometimes spoken of as Britain's best ever, Sir Charles Russell, a Catholic from Newry, Co. Down who eventually became Britain's lord chief justice despite being an Irish nationalist and a Catholic.

His defense of Parnell was called “the event of his life,” so well did he do, even with a court anxious to finish off Home Rule.

Russell’s cross-examination of Pigott has gone down in history. First, he asked Pigott to write down a few words and asked him to spell them.Pigott did so and at the end, Russell ever so casually asked him to write down the word “hesitancy.” Pigott did so and misspelled it as “hesitancy,” exactly as it had been in the alleged Parnell letter.

Then Russell took Pigott apart after Pigott claimed he knew nothing of the controversy before the letter appeared in the Times and that his only role was passing the letters along to the group who had hired him.

With great drama, Russell produced a letter Pigott had written to an archbishop days before the Times letters appeared in which Pigott stated they would appear in the Times and that he was perfectly aware of that fact.

Pigott’s story collapsed on the stand and the case fell apart. He admitted he had forged the letters and fled to Spain where he committed suicide, his plot to bring down Ireland’s “uncrowned king” in pieces.

It was fake news a la 1887, no different than today in terms of its intended impact. So nothing new it seems. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

*Originally published in December 2016, updated in 2024.

Comments