Christopher Quirin, 63, was born to a single mother in Ireland in 1950, a time when such a thing was widely considered an unspeakable disgrace. Back then Quirin’s mother was sent by her parents to the now notorious Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, Co. Tipperary, the same mother and baby home as Philomena Lee. Lee is the woman whose shocking life story inspired the Academy Award-nominated movie starring Judi Dench.

Lee and Quirin’s mother had children just two years apart, and Quirin says he imagines he must have played in the same rooms as Michael, Lee’s boy, who was later adopted by the American couple Doc and Marge Hess.

Unlike Lee, however, after beginning his new life in America, Quirin was left to piece together the details of the one he had left behind with no help from a dedicated senior journalist or the nuns at Sean Ross Abbey.

Because of the shame attached to their origins and the desire to prevent the birth mother from ever tracing her offspring at a later date, to this day adoption records have been closely guarded by the religious orders and the Irish state.

“For me, the process started back in the 1970s,” Quirin, who now lives in Long Island, New York, tells the Irish Voice.

“I was told by my mother I had been adopted. In a fit of anger actually. She said, ‘I wish we hadn’t adopted you.’ That kind of pushed me off the precipice.”

For Quirin, the coldness of his new adoptive home was the feature that he remembers most.

Read more: American nun sold as a child in Ireland tells her amazing story

“I knew I didn’t fit in,” he says. “I’m six feet tall with red hair and they were all short with brown hair. I used to think I was the milkman’s son.”

Not knowing who his birth family was, Quirin didn’t know anything about their medical history either. That fact, added to the memory of the tough time he’d had in his adoptive home, provided the impetus for him to begin his search for his birth mother.

“Every time I went to the doctor I had to put in A for adopted. I would have to explain my broken history each time. There comes a point when you get tired not knowing about your own family,” Quirin says.

“You should have the right to get access to your records and at least your medical records, I think. Then around 2009 I read "The Lost Child of Philomena Lee," but even that didn’t set me off. It wasn’t until the movie came out last year that I found the impetus to push me forward.”

Quirin’s father had kept his original adoption records (all of which were written in Irish). So with help from a network of adoption rights activists, Quirin was finally successful in doing something many others were not. He traced his birth mother's whereabouts.

“With help from an activist named Bernadette Joyce, I tracked her down. She did more in three days than the nuns had in decades. I had given donations to the nuns at Sean Ross Abbey from 1977 until recently when I finally gave up on them. They would not confirm or deny a single fact about my adoption.”

With his mother’s details in hand, Quirin flew to London and called on Margaret Linehan, 84, his birth mother.

“I literally ambushed her. I got on the tube, went out to her house, knocked on the door and started the relationship then.”

But Margaret Linehan wanted to keep her son a secret. She was not prepared to have a conversation about him with her children she said. In fact, she initially didn’t want to even speak to him.

“Away back to America with you!” she shouted at him from her kitchen window.

“I have a cynical view of the world,” says Quirin. “I took it with a grain of salt. I looked at her and I said, ‘Really?’ Then she came down and opened the door and we spent five hours together talking.”

Like Philomena Lee’s child, Quirin was the result of a teenage fling.

“Even though she had told her husband very early on in their relationship about me she didn’t want to do anything to disrupt her family at any point.”

Over time Quirin managed to convince her she had kept the secret long enough. “I said it’s about time you took the weight off your shoulders,” he recalled.

Margaret agreed, but she didn’t know how to do it. Eventually, she decided to talk to her daughter.

“I tried to call her over the next couple of days and couldn’t get a hold of her. All of sudden she called me out of the blue. She told me she had finally told them,” says Quirin.

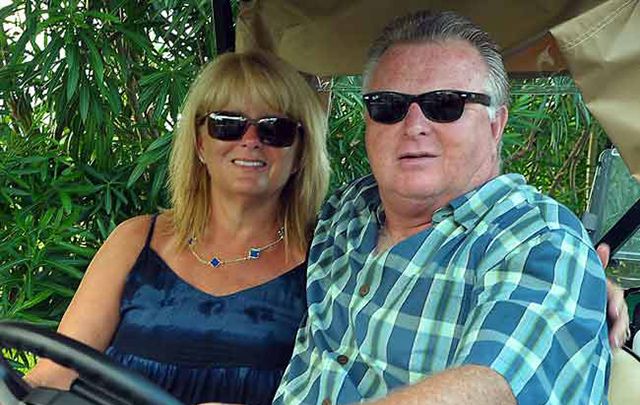

“So I sent her a bunch of photographs of myself and my wife and kids and she shared them with her family. She said it was as if a weight had been lifted off her.”

Later when Quirin visited they walked back to the train and Margaret became upset.

“She asked me what had been the bigger lie, being unwed and having a child – or denying for 63 years that you had a child? She said not a day went by when she didn’t think about me or wonder how I was doing. When I showed up she could see I was one of her own. I look like her other kids.”

Now Quirin says the way the nuns and religious authorities treated him has caused him to seriously doubt his relationship with the church.

“If you can turn a blind eye to 60,000 forced adoptions what else can you turn a blind eye to? Enough is enough.”

Has it damaged his faith? “In no uncertain terms. I was an altar boy, I went to Catholic school, I was raised in a Catholic home and they have taken that away from me. I’m having a very hard time squaring that circle.”

Once his mother told her children about Quirin their relationship was transformed. “She said to me, ‘I’m sorry I was such a bitch,’” he laughs.

“Now I have a real mother at last. It feels amazing. When I realized on the phone I was laughing hysterically, then when I got off the phone I was hysterically crying. But in some ways, I’m lucky I was adopted. I came to the U.S. and I’ve had a very successful life with a wonderful marriage and children.”

Growing up in his adoptive home there was a complete disconnect he says. “I never felt in any way emotionally close to the people who adopted me,” he reveals. “I left my home at 16 and stayed at my friend’s house until I got drafted, and after that, I never really became close to them again.”

But now finally Quirin has a mother. In fact, he also has two brothers and three sisters he’s about to meet.

“I’ll meet them for the first time this month. We’ll sit down in my mother’s house and meet the family. Then my daughter and son will meet them all this summer. They’ll see where their real family roots are.”

* Originally published in March 2014.

Comments