A heartbreaking Irish famine story of death and despair. A group of 600 Irish starving during the Great Hunger set out to Doolough to find food. Most of them did not survive.

Our guide has told the same story perhaps a thousand times yet still it brought a lump to her throat.

“People around here recall that in 1849 folks living in my hometown of Louisborough in Co Mayo - around 600 in total and including women and children - were starving as a result of the potato famine and a rumor went around that, if they walked to Delphi Lodge where the landlord and council of guardians were, then they’d be given food,” she said.

“It’s about 15 miles and a very beautiful walk today by the shores of the Killary and Doolough lakes. But it was bleak and freezing when those people set out on that night on their journey to meet their landlord.

“So they set out and walked anyway in atrocious conditions and literally died on the way back of weakness and starvation. Later, people found corpses by the side of the road where you’re standing with grass in their mouths that they had been eating for want of food.

“When the people had eventually got to Delphi Lodge, they were told that the guardians could not be disturbed while they were taking their lunch. When they finally did see them, the people were sent away empty-handed and most of them died on the journey back.”

Doolough Valley, County Mayo.

We all went quiet for a moment.

Then our guide continued: “It makes me very sad and very angry.”

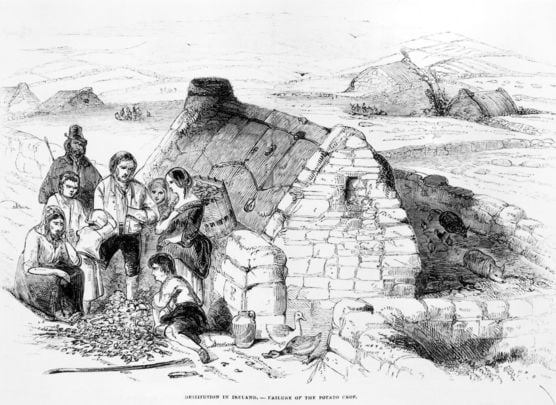

The Great Hunger - An Gorta Mor - is the biggest tragedy to have hit Ireland. Between 1845 and 1850 an estimated one million people died there when the staple potato crop failed. If you add forced emigration to the USA, Canada and elsewhere to that figure which followed as a result, Ireland’s total population was cut by around a quarter as a direct cause of the Famine.

There are a number of versions of the Doolough Famine Walk of 1849, as it has become known, in which the numbers of people and the circumstances of their deaths vary tremendously. We rely on a letter published in the Mayo Constitution of April 10, 1849, signed by ‘A Ratepayer’, which first blew the whistle on the case.

It describes how in late March of that year, Colonel Hogrove, a member of the Board of Guardians (who administered the Poor Relief), and Captain Primrose, the local Poor Law inspector, arrived in Louisborough to inspect those claiming relief.

People came to the town from all around only to find that the two men had headed south to Delphi, where at that time stood on the shores of Doolough lake the hunting lodge of the Marquess of Sligo. It’s thought the two men had gone to Delphi to go hunting. They gave instructions for people to gather there for the inspection instead, or face being struck off the poor relief register.

The letter writer went on to call for an inquiry into the ‘melancholy affair’.

Louisborough today is a small friendly town. Four miles away is Croagh Patrick, Ireland’s holiest pilgrimage site, at the foot of which is Ireland’s National Famine Memorial. It’s a sad metal structure of a three-masted ship, the sort that took people to the New World back then. They became known as coffin ships. Around the structure skeletal figures of the starving stand pleading.

And then we continued our journey onwards to Delphi in the footsteps of our ancestors as we walked our way through history.

The inky waters of Doolough came into view and then three hills in the distance upon one of which you could still make out the scant edges of the old potato fields. Two memorials marked the spot where the disaster happened. One a plain stone cross engraved with the words ‘Doolough Tragedy 1849’. The other carried another inscription: “To commemorate the hungry poor who walked here in 1849 and who walk the Third World today.

A road running through Doolough Valley, County Mayo.

Every year since 1988 there has been a walk along this route in memory of the Doolough dead and to highlight the starvation of the world’s poor still today. Archbishop Desmond Tutu has done it, the children of Chernobyl have done it. So has the Cellist of Sarajevo, Vedran Smailovic who played daily in his city despite sniper fire in the 1990s while it was under siege. And Kim Phuc - the woman who was made famous in photographs of her as a girl running naked and burned by napalm in Vietnam - she has done it too.

As have Native American Indians. When they learned of the tragedy in 1849, members of the Choctaw tribe raised $710 which they donated to Irish famine relief. They did so because the story reminded them of their own plight when, 18 years earlier, they were forcibly removed from their land by the white man to make way for modern-day Oklahoma. Their march was some 500 miles and they lost lives along the way. The Indians’ march became known as the Trail of Tears.

In 1992 a group of Irish people returned the Choctaw Indians’ kindness by walking the Trail of Tears, raising a huge $710,000 which they donated to famine relief in Africa.

The annual commemoration of those events of March 1849 leading to the Doolough Tragedy ensures the people’s sacrifice in these parts will never be forgotten.

* Originally published in 2016. Updated in Feb 2023.

Comments