In June 1986, then-rising filmmaker Terry George went to the first concert played in New York City by the Irish folk group called The Pogues who were gaining cult status in Britain. It proved to be quite a night.

On a sweltering night in June 1986, some 2,000 New Yorkers, myself included, crowded into the Ritz Ballroom in New York City’s East Village to hear the world's only punk rock ceili band.

The throng at the door was an even mix of green cardless and green spiked hair. Scalpers were asking $50 for a $15 ticket and getting $45.

View this post on Instagram

The cause of all the excitement was an eight-piece London Irish band called The Pogues. Originally they were the Pogue Mahones until the BBC found out that meant ‘Kiss My Ass” in Irish.

The origins of The Pogues can be traced to a jamming session at a London rock venue, Cabaret Futura, where Shane MacGowan, the former leader of the punk band The Nipple Erectors, joined tin whistle player Spider Stacey in a rendition of Irish folk and rebel songs.

The duo then teamed up with banjo player and subway musician Jem Finer accordionist Andrew Ranken female vocalist and bass player Cáit O’Riordan and the only Irish-born musicians in the group, Phil Chevron and Terry Woods.

The Pogues quickly gathered a cult following in London as word spread they were the best live band around.

The secret of their success is Irish folk standards like "Poor Paddy," "The Auld Triangle," and "Dirty Old Town," a raucous mix of bluegrass, cajun accordion, and wild, inspired tin whistle.

The Pogues sound like the Shankill Road Defenders Orange pipe band run amok.

The beat is pulsating, unrelenting and then there are the lyrics.

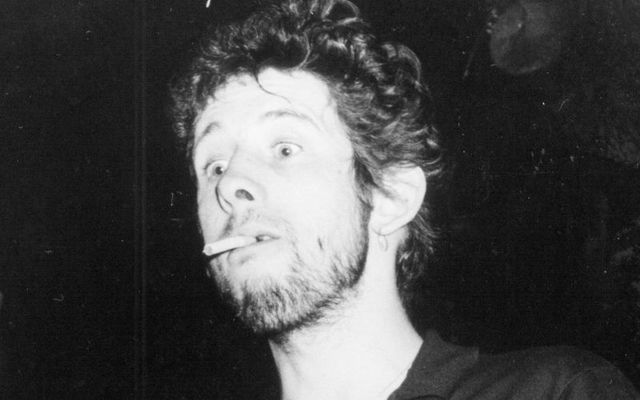

Lead singer Shane MacGowan had a voice that might have been nurtured on pints of Guinness laced with iron filings. It matched the tempo perfectly. You can almost hear their version of "The Auld Triangle" being belted out of a barred cell in The ‘Joy (Dublin's Mountjoy Prison) on a foggy night, defying every screw and cop in Ireland.

When MacGowan sings "Dirty Old Town," he evokes pictures of vandalized factory ruins and polluted waterways. This is not the sentimental hometown version of the songwriter Ewan MacColl.

MacGowan and The Pogues have caused considerable controversy in Irish music circles.

Christy Moore considered them to be the future of Irish Folk while one member of De Dannan denounced them as absolute rubbish.

One thing is certain. MacGowan did his best to drive off the Aran sweater image of Irish folk music. The man possessed the worst set of teeth this side of George Washington’s wooden dentures and he loved to flash them to the camera.

He was known to stagger onto the stage carrying the preferred beverage of the night. On this occasion at The Ritz, it was a gallon bottle of Folona Soave. He drank it all by concert’s end.

Despite the stage image and the howls of outrage by the purists, the band managed a crossover that other groups such as Horslips, Thin Lizzy, and Stockton’s Wing never quite achieved.

By the end of the night at the Ritz, leather-jacketed bikers were dancing jigs as orange-haired punk teenagers joined in reels to the beat of "Poor Paddy."

Bras started landing on the stage, an event guaranteed to stop a Chieftain’s concert in its tracks.

This was Ceili for the 80s. The band had given a session as raucous, wild, and uplifting as any seen at a recent Fleadh Cheoil.

Moreover, MacGowan had demonstrated that not only can he drink a gallon of cheap wine and still stand, but he also happened to be a social commentator of some considerable power.

On this night, it was almost impossible to hear the lyrics but there, behind the wall of Cajun accordion, banging banjos, and basuki were words of a boy prophet, an unemployable poet.

His "Billy’s Bones” tells the story of the young hard man given to beating up cops who joins the Irish Army and ends up in Lebanon: "Billy went away with the peace-keeping force / 'Cause he liked a bloody good fight, of course."

"Now Billy's out there in the desert sun

And his mother cries when the morning comes

And there's mothers crying all over this world

For their poor dead darling boys and girls."

MacGowan wrote words for the times, a time of unemployment and random violence, racism, war in Northern Ireland, huge deprivation in the south, and deep suspicions of Irish emigrants in Britain because of the IRA campaign.

They arrived on the progressive Irish folk scene and gave it a well-needed kick up the Mahone.

*Terry George is an Oscar-winning director, major films include "In the Name of the Father," "Hotel Rwanda" and "The Boxer."

Comments