At 8:45 AM on October 16, 1962, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy alerted President John F. Kennedy that a major international crisis was at hand.

Russia had secretly placed nuclear missiles in Cuba, just 90 miles from the Florida coast. America could soon be under deadly attack. His adversary Nikita Kruschev was certain he had the measure of the young president, who ultimately proved the Soviet Premier wrong.

Kennedy had learned to be wary of the military experts after the botched invasion of Cuban exiles trying to remove Castro who were driven back at the Bay of Pigs.

That experience would stand to him greatly during the 13 days in October 1962 when Armageddon threatened.

The following is how the crisis is unfolded, in part by the JFK Presidential Library:

Two days earlier a United States military surveillance aircraft had taken hundreds of aerial photographs of Cuba. CIA analysts, working around the clock, had deciphered in the pictures conclusive evidence that a Soviet missile base was under construction near San Cristobal, Cuba; just 90 miles from the coast of Florida.

Aerial shots of Cuba taken in October 1962 (Getty Images)

The most dangerous encounter in the history of the world and the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union had begun.

For thirteen days in October 1962, the world waited—seemingly on the brink of nuclear war—and hoped for a peaceful resolution to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Meanwhile, the US moved its readiness for war to DEFCON 2 the last step before a nuclear war. It was going to be a white-knuckle two weeks.

The thirteen days marking the most dangerous period of the Cuban missile crisis began. President Kennedy and principal foreign policy and national defense officials are briefed on the U-2 findings.

Discussions begin on how to respond to the challenge. Two principal courses are offered: an airstrike and invasion, or a naval quarantine with the threat of further military action. To avoid arousing public concern, the president maintained his official schedule, meeting periodically with advisors to discuss the status of events in Cuba and possible strategies.

On Day 2, American military units began moving to bases in the Southeastern U.S. as intelligence photos from another U-2 flight show additional sites; and 16 to 32 missiles. President Kennedy attends a brief service at St. Matthew's Cathedral in observance of the National Day of Prayer.

After, he has lunch with Crown Prince Hasan of Libya and then makes a political visit to Connecticut in support of Democratic congressional candidates.

On Day 3, President Kennedy is visited by Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, who asserts that Soviet aid to Cuba is purely defensive and does not represent a threat to the United States. Kennedy, without revealing what he knows of the existence of the missiles, reads to Gromyko his public warning of September 4 that the "gravest consequences" would follow if significant Soviet offensive weapons were introduced into Cuba.

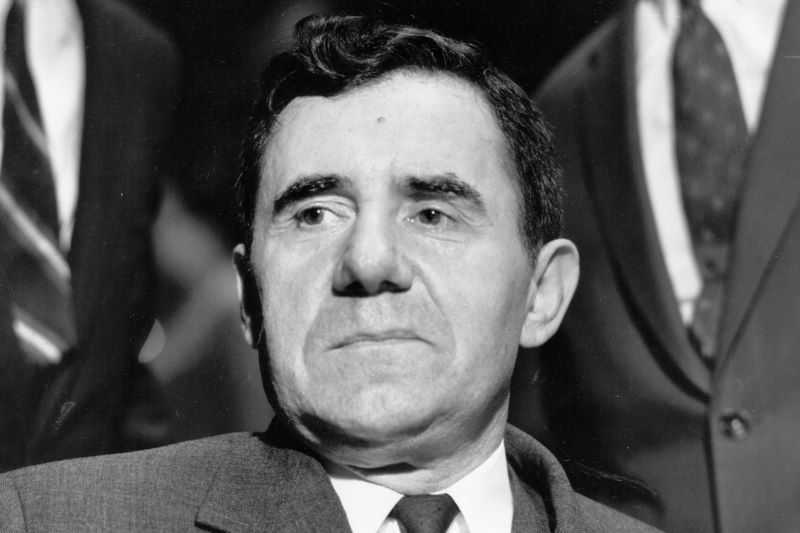

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko (Getty Images)

Day 4 was spent in discussion with his advisors, and on Day 5 President Kennedy returns suddenly to Washington. After five hours of discussion with top advisers, the President decides on the quarantine and blockade. Plans for deploying naval units are drawn and work is begun on a speech to notify the American people.

On Day 6, after attending Mass at St. Stephen's Church with Mrs. Kennedy, the President meets with General Walter Sweeney of the Tactical Air Command who tells him that an airstrike could not guarantee 100% destruction of the missiles.

On Day 7, President Kennedy phones former Presidents Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower to brief them on the situation. Meetings to coordinate all actions continue. Kennedy formally established the Executive Committee of the National Security Council and instructed it to meet daily during the crisis. Kennedy briefs the cabinet and congressional leaders on the situation. Kennedy also informs British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan of the situation by telephone.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

At 7:00 p.m. Kennedy speaks on television, revealing the evidence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and calling for their removal. He also announces the establishment of a naval quarantine around the island until the Soviet Union agrees to dismantle the missile sites and to make certain that no additional missiles are shipped to Cuba. Approximately one hour before the speech, Secretary of State Dean Rusk formally notifies Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin of the contents of the President's speech.

On Day 8, the ships of the naval quarantine fleet move into place around Cuba. Soviet submarines threaten the quarantine by moving into the Caribbean area. Soviet freighters bound for Cuba with military supplies stop dead in the water, but the oil tanker Bucharest continues towards Cuba. In the evening Robert Kennedy meets with Ambassador Dobrynin at the Soviet Embassy.

Russian Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Federovich Dobrynin (Getty Images)

On Day 9, Kruschev threatens war. He writes to Kennedy: "You, Mr. President, are not declaring a quarantine, but rather are setting forth an ultimatum and threatening that if we do not give in to your demands you will use force. Consider what you are saying! And you want to persuade me to agree to this! What would it mean to agree to these demands? It would mean guiding oneself in one's relations with other countries not by reason, but by submitting to arbitrariness. You are no longer appealing to reason, but wish to intimidate us."

President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev, pictured here circa 1960 (Getty Images)

On Day 10, knowing that some missiles in Cuba were now operational, the president personally drafts a letter to Premier Khrushchev, again urging him to change the course of events. Meanwhile, Soviet freighters turn and head back to Europe. The Bucharest, carrying only petroleum products, is allowed through the quarantine line. U.N. Secretary General U Thant calls for a cooling-off period, which is rejected by Kennedy because it would leave the missiles in place.

On Day 11, a Soviet-chartered freighter is stopped at the quarantine line and searched for contraband military supplies. None are found and the ship is allowed to proceed to Cuba. Photographic evidence shows accelerated construction of the missile sites and the uncrating of Soviet IL-28 bombers at Cuban airfields.

A Soviet cargo ship with eight missile transporters and canvas-covered missiles lashed on deck during its return voyage from Cuba to the Soviet Union. (Getty Images)

In a private letter, Fidel Castro urges Nikita Khrushchev to initiate a nuclear first strike against the United States in the event of an American invasion of Cuba.

May 7, 1964: Cuba's Fidel Castro with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev at the Lenin Mausoleum in Red Square, Moscow. (Getty Images)

John Scali, ABC News reporter, is approached by Aleksander Fomin of the Soviet embassy staff with a proposal for a solution to the crisis.

Later, a long, rambling letter from Khrushchev to Kennedy makes a similar offer: removal of the missiles in exchange for lifting the quarantine and a pledge that the U.S. will not invade Cuba.

On Day 12, the second letter from Moscow demanding tougher terms, including the removal of obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey, is received in Washington.

Over Cuba, an American U-2 plane is shot down by a Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile and the pilot, Major Rudolph Anderson is killed. President Kennedy writes a letter to the widow of USAF Major Rudolf Anderson, Jr., offering condolences, and informing her that President Kennedy is awarding him the Distinguished Service Medal, posthumously.

On Day 13, the thirteen days marking the most dangerous period of the Cuban missile crisis ended. Radio Moscow announces that the Soviet Union has accepted the proposed solution and releases the text of a Khrushchev letter affirming that the missiles will be removed in exchange for a non-invasion pledge from the United States.

The young American leader faced down the Soviet Union and avoided nuclear war in the process. In refusing to use nuclear missiles Kennedy went against at least one of his own advisors but saved the world from incredible destruction.

General Curtis LeMay of the Joint Chiefs had told Kennedy that the course the President had settled on–a naval blockade of Cuba–was a bad idea and was “almost as bad as the appeasement at Munich.” At another point of this November 16 meeting, he advocated “solving” the problem, by which he meant implementing CINCLANT OPLAN 312-62, the air attack plan for Cuba.

* Originally published in 2015, updated in 2023..

Comments