Editor's note: The text that follows appeared in the Irish Voice on March 29th 2017 as a letter to the Editor.

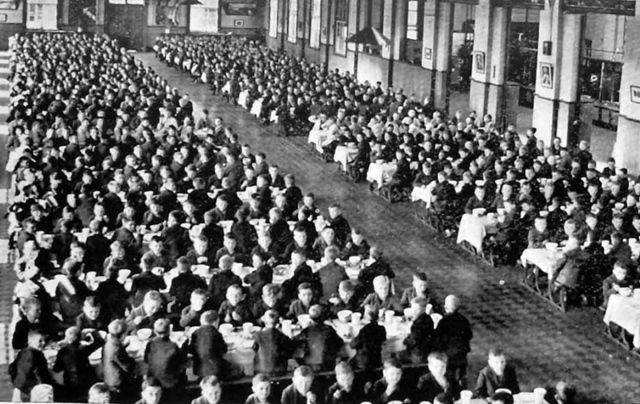

I recall clearly a shocking conversation that I had about 20 years ago, with a fine man from Tralee, Co. Kerry about the Christian Brothers Industrial School in that town. He recalled that some of the boys confined in the industrial school attended classes with him in The Green, the brothers' local high school. He remembered that when the final bell rang to end the school day they would bolt for their living quarters because if they tarried at all they claimed they would be beaten.

My other memory of that conversation is much more disturbing. He told me that local people would sometimes hear screams at night from the school. As a teenager, he was surprised by this and asked his father, who worked as a laborer in the town, what was going on to cause such nocturnal cries.

His father replied that such matters were beyond his ability to deal with and that his son was better not talking about them -- a very understandable response in those times.

The scene of boys crying out for help to a deaf and seemingly uncaring community in my own county 50 or so years ago, is seared in my memory. The men in clerical robes were paid by the state and honored for their work by the local clergy and dignitaries.

Completely disregarded was the clear admonition of the 1916 leaders that the country they fought and died for must "treat all the children of the nation equally." Poor, marginalized kids who had nobody to speak for them cried out in pain and nobody answered -- the stuff of nightmares.

I was reminded of these poor boys by three recent related reports, one from the Vatican and one each from Australia and Ireland.

Three years ago, Pope Francis responded to the sordid stories from all over the world of children being sexually abused by priests and brothers by setting up a high-powered commission with a mandate to develop policies and recommendations to protect children. This distinguished group, led by papal favorite Cardinal Sean O'Malley from Boston, included two victims of clerical abuse, Peter Saunders, a Briton, and Marie Collins from Dublin.

Saunders, who was abused by two priests as a teenager, cast a cold eye on the commission, describing it as mainly a public relations exercise by church leaders, and he was outspoken in his criticism of senior curia officials, including Australian Cardinal George Pell. He was removed from the committee last year. He berated the whole Vatican bureaucracy, including the Pope, for lack of urgency in dealing with the clerical abuse crisis.

Recently Collins, who was repeatedly sexually abused by a priest from age 13 in Dublin, resigned from the papal group for basically the same reasons as Saunders. She explained that she was tired of "constant setbacks" from the various curias who "thrive on silence and cover-up." She said that she doesn't doubt Francis' sincerity and commitment but that it is unacceptable that "men at this high level in the church do not see child protection as a priority."

It certainly doesn't augur well for the effectiveness and credibility of O’Malley’s Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors that the two members who could testify from bitter experience about the terrible effects of clerical child abuse have resigned.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse in Australia reported a few weeks ago. The Catholic community there is in shock because the results show that children assigned to Catholic institutions fared very poorly in this area of child protection.

The headline in many newspapers highlighted the finding that an astonishing 40 percent of St. John of God Brothers abused their young vulnerable clients. The results for the Irish Christian Brothers were better at 22 percent; Marists and De La Salles came in at about half of that and "only" one in 14 priests disgraced themselves by becoming predators instead of defenders of vulnerable children.

The third and most recent account which relates to the Bon Secours Home in Tuam, Co. Galway, was even more incredible and mind shattering than the Australian report.

Details emerged of about 796 bodies of dead children, buried in pits adjoining the sewerage system in Tuam in one of the nine Catholic mother and baby homes throughout Ireland. This "home" was under the care of the Bon Secours Sisters who are still active in Ireland.

Taoiseach Enda Kenny spoke passionately in the Dail about "the chamber of horrors" in Tuam. He said, “We took their babies and gifted them, sold them, trafficked them, starved them, neglected them or denied them to the point of their disappearance from our hearts, our sight, our country."

Two big questions must be asked about what went on in these "homes" and "schools" in Ireland and Australia. How did priests and nuns and brothers, supposedly committed to high-level Christian living, trained in strict Catholic novitiates, perform such awful acts, including in some cases starving and buggering the children in their care?

Why did some of them not cry stop? How do you explain the group depravity and corruption pervading these awful Catholic institutions?

The second question relates to the public authorities because these religious orders were paid for their services out of the public purse. Inspectors visited the industrial schools but bought the lies of the men responsible for running them.

Ironically, boys in these so-called reformatories in Northern Ireland had a better chance of some level of humane treatment because the British inspectors were less likely to accept the palaver of the people in charge.

Famous Irish priest Father Flanagan of Boys Town fame visited Ireland in the forties and realized that there were major problems in the industrial schools. He addressed the issues, stressing the positive policies he followed in his program for similar troubled youth in Nebraska.

No bishop spoke out in his favor, and he was rebuked publicly in the Dail as an outside troublemaker by the then Minister for Justice Gerard Boland.

Apart possibly from the Irish Civil War, the complete abandonment of humane and Christian principles in dealing with the most vulnerable young people is by far the biggest stain in the Irish people's story since the country achieved independence in 1922.

* Gerry O’Shea, Yonkers, New York.

Comments