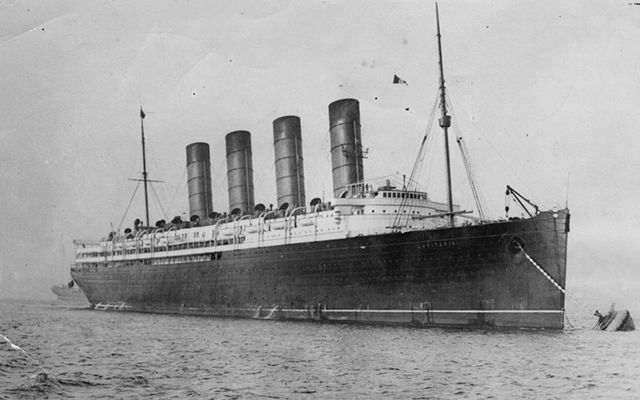

On May 7, 1915, tragically 1,201 people died after the RMS Lusitania, a passenger ship, was hit by a German U-boat torpedo off the coast of Cobh, County Cork.

The anniversary of the sinking of the great liner the Lusitania a few miles off the Irish coast, in May 1915, is a time of sad reflection for many people here.

I've been reading a book that vividly brings to life the horror of what happened when the ship was torpedoed and over 1,000 men, women, and children perished in the waters within sight of the Old Head of Kinsale in County Cork.

The book is "Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania," written by New York Times reporter and narrative historian Erik Larson. It's a remarkable piece of storytelling and I strongly recommend it.

Among the controversial issues raised in the book is the possibility, even the likelihood, that Winston Churchill was largely responsible for the sinking, not by any action of his but by inaction. He knew about the danger and there were a number of actions he should have taken which would have avoided the disaster, yet he deliberately did nothing. But we will come back to that in a moment.

A painting illustrating the sinking of the Luisitania.

First I should mention Larson's extraordinary ability to bring history alive, an example being the way he describes the horrified fascination of people on board the ship who actually saw the torpedo approaching.

A seaman lookout first spotted "a burst of foam about 500 yards away," then a track moving across the flat plane of the sea as clear as if it had been drawn "by an invisible hand."

It was just after 2 p.m. The sun was shining; the sea was like glass; the Irish coast was visible just over 10 miles away and passengers were strolling on deck after lunch.

Some of them also saw the torpedo approaching. One noticed "a streak of froth" arcing across the surface towards the ship. Another leaned over the rail to watch what would happen when it hit the side. He described the torpedo as "a beautiful sight,'' covered with a silvery phosphorescence as it sped through the green water.

A woman asked, "That isn't a torpedo, is it?" The man beside her later said, "I was too spellbound to answer. I felt absolutely sick."

It was surreal. The giant steamer was just a few miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, slicing through the perfectly calm water on a beautiful afternoon.

But despite the feeling of unreality this was indeed the very thing that everyone on board had silently feared and joked nervously about since they had left New York five days earlier, on May 1, 1915, bound for Liverpool. What followed was appalling as the ship went down in just 18 minutes and 1,198 people perished.

Three years earlier 1,514 people had died when the Titanic hit an iceberg, and that tragedy has remained in the public imagination ever since. The sinking of the Lusitania, however, has largely been forgotten. Yet the story is just as horrific as that of the Titanic.

And if you're wondering about the title of the book, "Dead Wake," it refers to the visible trail of the torpedo on the surface formed by bubbles of compressed air released from the torpedo engine 10 feet below. The bubbles take several seconds to reach the surface so the wake is “dead” because by the time it forms the torpedo is far ahead of it.

The fact that we know the outcome does not lessen the impact of this book, which at times is as gripping as a thriller. Larson builds the story from several perspectives at the same time, switching between what is going on in different places in short scenes.

It is the story mainly of the hunter and the hunted, the U-boat and the liner. But it is also the wider story of the depressive, lovelorn President Woodrow Wilson, reluctant to enter the war, and the young Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, determined to get America involved.

Early on we meet some passengers, including glamorous types like the multi-millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt, the “Champagne King” George Kessler, and the Boston bookseller Charles Lauriat, who was carrying Charles Dickens's own copy (priceless) of "A Christmas Carol."

Also on board was Dublin art collector Sir Hugh Lane with a large case of paintings rumored to have included works by Rubens, Monet, and Rembrandt which was insured for the equivalent of over $90 million today.

In retrospect, it may seem foolhardy to have been traveling at the time at all since the Great War had started the year before in 1914. But all the passengers had their way of rationalizing away the danger despite an American newspaper notice that had appeared right beside an ad for the Lusitania's voyage shortly before the ship sailed.

In the notice, the German government had warned that the shipping lanes around Britain were now a war zone and that ships were "liable to destruction." German U-boats were known to be active in the area.

Read more

Yet few passengers early in 1915 believed that the Germans would actually attack a passenger liner. Even if the Lusitania were attacked, it was twice as fast as a submarine and could outrun any danger, they told each other.

They also believed that a Royal Navy escort would be provided as soon as the Lusitania neared Ireland. Despite all this, nervous chatter about submarines continued among passengers throughout the voyage.

Larson explains the coincidence of circumstances that led to the disaster – why the Lusitania was late leaving New York, why it was sailing parallel to the Irish coast at less than maximum speed, how it accidentally came within range of the submarine, how fog cleared at the crucial time, why the U-boat was there instead of where it was supposed to be near Liverpool.

He is very good at describing the complex workings of the steam-driven Lusitania – one of the great "trans-Atlantic greyhounds' – and the limitations of the early submarines like the U-20 which sank it.

The details of the converging voyages of the Lusitania and the U-20 have a horrible fascination because as a reader, even though you know what is coming, you keep hoping that somehow they will miss each other. The sinking and its aftermath are brilliantly described using the accounts of survivors, the U-boat captain's log and recently released documents from the two main inquiries into the disaster.

Because of the ship's rapid listing, only six of the 23 lifeboats were successfully launched, many people were crushed by debris and there was no ship in the area close enough to pick up people in the water in time. Small sailing craft from Kinsale did their best but, partly because of the calm day, they were too slow.

As well as telling a compelling story, Larson also deals with the suspicion that, because there was a second powerful blast inside the ship after the torpedo had exploded, the Lusitania must have been carrying explosives. It was – 170 tons of rifle ammunition and 1,250 cases of artillery shells, as well as 50 barrels each of flammable aluminum and bronze powder – all of which was legal under U.S. neutrality rules at the time.

It may sound like a lot, but it was not a significant amount in terms of war supplies. And it certainly did not provide any retrospective justification for the sinking which claimed over 1,000 civilian lives.

Men digging grave for the dead after the sinking of the Luisitania, in Cork.

Larson also explains why it is most unlikely that any of this material exploded – the artillery shells were minus their charges, for example – and why the second explosion was caused either by the ignition of coal dust in the ship's vast bunkers, then nearly empty, or cold seawater hitting the superheated boilers and pipes.

But the most interesting part of the book by far is the section in which Larson reveals the workings of the secret Room 40 in an old Admiralty building in central London, the center of a covert operation run by Churchill which was monitoring and decoding German naval radio messages. This clearly shows that Churchill and the very senior people in the Admiralty knew all about U-20 and roughly where it was and the extreme danger it posed to the approaching Lusitania.

Yet nothing was done to protect the liner and its passengers, even though Room 40 knew that 23 British merchant ships had been torpedoed around the coast of Britain and Ireland in the preceding seven days, three of them by the U-20.

At the same time as Lusitania was approaching Ireland, several destroyers were being used to protect the pride of the British navy, the battleship Orion, which had just left port. Other destroyers that could have protected the Lusitania were tied up in British and Irish ports.

Given all that Room 20 knew about submarine activity in the area at the time, the Lusitania should have been diverted to the safer North Channel route (around the top of Ireland). It also should have been given a naval escort as it approached from the Atlantic.

Neither was done and this looks very suspicious, given earlier remarks made by Churchill implying that it would take a major disaster to get America into the war. The sinking of the Lusitania, with many Americans on board, provided such a disaster.

If the sinking of the Lusitania was, as it appears, a result of deliberate and calculated inaction by Churchill, it surely must rank among the greatest sins of omission ever committed.

* Originally published in 2015.

Comments