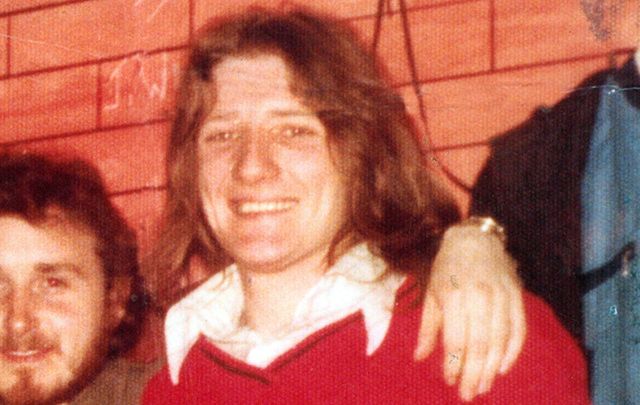

"Bobby Sands: 66 Days" is the acclaimed new documentary focusing on the Irishman who has become an undisputed icon of 20th-century political activism.

Directed by Brendan Byrne, the film explores Sands’ background, philosophies, and the fateful decision he took to lead his fellow inmates on a hunger strike that changed the course of Irish history. Cahir O’Doherty speaks to Byrne about the film, which has already become Northern Ireland's most successful documentary film ever.

This month "Bobby Sands: 66 Days," the acclaimed new documentary film, tells the story of the Belfast-born hunger striker, now indisputably one of Ireland’s most iconic political figures.

Using eyewitness testimony and previously unseen archive material, director Brendan Byrne’s ambition is to provide the definitive account of the life and legacy of the self-created Irish martyr.

Most critics agree that Byrne, 49, has successfully achieved his aim. "66 Days" is a thoughtful, considered, and remarkably even-handed telling of how and why Sands decided to go on hunger strike and what his decision meant for the country.

It took just over two months for Sands’ hunger strike to run its course, and the prevailing attitudes about it (and him) largely depend on where you stood.

If you were nationalist you may have grieved for a mother who had lost her child as well as for a prisoner making a legitimate political protest. If you were a republican you were mourning the loss of an icon, an embodiment of the national struggle.

But if you were unionist or loyalist Sands was at best a canny political player, and at worst a conniving terrorist.

What’s remarkable is that so many different people could hold such widely divergent opinions about the same man.

So in "Bobby Sands: 66 Days," Byrne grapples with this multifaceted and transformative figure in an even-handed portrait that gives voice to all strands of opinion.

Knowing how divergent and contradictory public attitudes to Sands and his hunger strike would be, what compelled Byrne to make the film? “With the exception of Hunger, a film about Sands hadn’t been made in detail,” Byrne tells the Irish Voice.

“For a long time, he was still too controversial a figure for many people. The people who you had to turn to for the money to make it just couldn’t go there yet.”

In Ireland and the UK, there is peace, but there’s been much less reconciliation after the long war and no great efforts have been made to do anything about it, Byrne says. That stalemate is only now being broken, particularly by younger people.

Although Byrne admires the award-winning Hunger (with Michael Fassbender starring as Sands), he calls it an experiential film about a hunger striker which mainly focuses on what it must be like to starve oneself to death.

“For me, it passed over questions of who the guy was. I’m almost 50 years of age and I grew up in a working-class community in Belfast, and I realized I didn’t know much about Sands other than the face I’d see on the gable wall. So I thought for all those reasons it was time to open up the chapter again and take a fresh look,” Byrne says.

May 5, 1981, was an unforgettable day for any Irish person who lived through it. It began with the morning news reports informing the nation (and the world) that Sands had died.

In the villages, towns, and cities across the whole island, many will recall the strange solemnity that descended. People were bracing themselves. The worst had just happened, and what The Troubles had taught us was the worst was usually just a prelude.

“A hunger strike is a line-in-the-sand gesture, it’s for when you are having a serious fight with your opponent. You have literally nothing else but your body to fight against the might of the British government. I think in some ways it was the only option Bobby Sands felt he had,” says Byrne.

“He only took this path because his colleagues and comrades who had chosen to take it demonstrated that individually they weren’t prepared to go to the very end.

“He knew if this was going to be a tactic the republican movement was going to be successful in he could only trust himself. That decision was even against the wishes of the IRA leadership.”

In the film, Byrne makes time for Sands’ life before the conflict that would come to define him, and in this way he allows much more of the human dimension to emerge.

"66 Days" is so illuminating because it reflects on an ordinary life lived in the silent eye of a tragic conflict. Through his own words, poems, letters, and “comms” from inside prison, and with particular reference to the personal diary he kept for the first 17 days of his hunger strike, Sands the man slowly emerges from the shadow of his own myth.

“The few criticisms the film has received to date have been really minor in relation to the acclaim it has received,” Byrne explains. “Within a section of the insular unionist community, Bobby Sands is someone they don’t want to have to reckon with, because they don’t have a charge sheet that proves he murdered someone, and because he’s a guy who starved himself to death for something he believed in.”

There’s no good time in their books for an exploration of Bobby Sands's life, no explanation is ever going to be good enough for those guys, Byrne says.

“If anything all they did was help us, because they went to the press, shouted about a film they never saw, and whipped up a huge amount of free publicity. Loads of people went to see the film as a result.”

Mainstream British newspapers found the film balanced and well made, however.

“I think by and large it has been rightly singled out as not being afraid of being sympathetic to Sands without being sympathetic to the IRA, but more importantly it gives the other side. It’s not only a one-sided perspective,” Byrne says.

The film also includes Charles Moore, the former editor of The Daily Telegraph and Margaret Thatcher’s biographer. “By including such divergent voices we really made ourselves immune from anything other than low-grade criticism,” Byrne says. (The BBC is the film’s main funder, a fact that Bryne also thinks speaks for itself).

Sands’ own words are quoted extensively, opening a window into his beliefs, putting his voice at the center of the film, and taking us inside his head, the only place where he found freedom.

What does Byrne think of his subject now that he has taken the time to speak to those who knew him, read Sands in his own words, and reflect on his actions?

“I was a 15-year-old school boy the year he died. I was going home from school and there were protests and thousands of people on the streets. I knew something seismic was happening that I couldn’t fully process,” Byrne recalls.

“But the images from 1981 became indelibly etched in my mind, and going back to make the film was going back to make sense of the history of that period and the country I grew up in.”

Byrne attributes Sands’ sacrifice to the birth of Sinn Fein and the path toward nonviolence and the peace process.

“In some ways, it prolonged the war and propelled the peace at the same time,” says Byrne.

"Bobby Sands: 66 Days" will open at the Film Forum in New York on November 30.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments