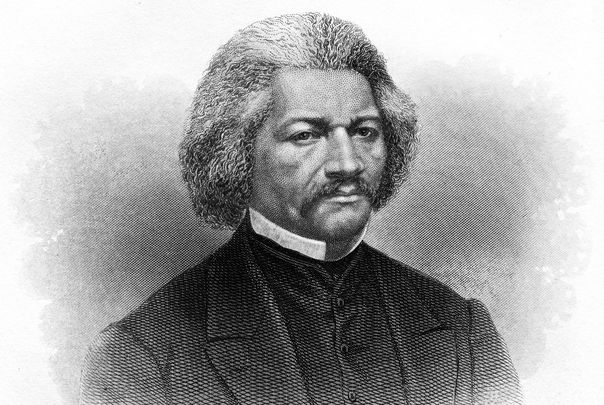

Ireland's emancipation movement exerted a great influence on iconic African-American Frederick Douglass.

There was a time in Ireland, not so long ago, when seeing a person of color was a noteworthy occurrence. So you'd think that Black History Month wouldn't have much relevance here.

But you'd be mistaken.

In August 1845, former slave Frederick Douglass set sail from Boston for a two-year lecture tour of the British Isles, commencing with four months in Ireland – including a meeting with Irish nationalist leader Daniel O'Connell – that would have a transformative effect on the famous abolitionist's subsequent life and career.

The plain facts of Douglass' extraordinary United Kingdom and Ireland tour – arranged primarily to escape the increased threats of kidnapping and bodily harm brought on by the publication of his best-selling autobiography – are available to anyone with a working laptop and a functioning WiFi connection.

But if you'd like a literary take on what Douglass felt and thought and experienced during his time in Ireland – which, by late 1845, was a country on the brink of full-blown famine – then allow me to suggest Colum McCann's episodic 2013 novel, TransAtlantic.

In the chapter entitled “freeman,” McCann gives a vivid account of Douglass's visit to the Emerald Isle – which begins inauspiciously in Boston when the one-time slave is “forced into steerage on the steamer Cambria even though he had tried to book first class.”

The UK was a sensible enough destination for an abolitionist campaigner – in 1807 Parliament had prohibited any British involvement in the slave trade and then in 1833 outlawed the practice itself in most of the empire's overseas colonies – but why was Douglass bothering with Ireland?

According to McCann, Douglass had good reason to include Ireland in his tour.

“The Irish abolitionists were known for their fervor. They came from the land of O'Connell, after all. The Great Liberator. There was, he'd been told, a great hunger for justice.”

In comparison to Boston, “even in Massachusetts he was still chased down the street, beaten, spat upon”.

Douglass finds Dublin a welcoming place where he is no longer a piece of property but a rightful man. His appearance alone marks him out – thanks to a rigorous exercise regime, the 27-year-old Douglass is “broad-shouldered, muscled, over six feet tall” – and when he arrives at the home of his Dublin publisher, he is met with courtesy and deference befitting an international celebrity.

But it is Douglass's brief acquaintance with Daniel O'Connell – “Ireland's truest son,” just turned 70, who “had adventured his life for proper freedom” – that opens his mind to the possibility of universal human rights.

At a rally in Dublin Douglass is brought onstage and introduced by the Great Liberator himself as “the black O'Connell.”

When a shout comes from the rear of the hall – “What about England...Was there not an underground railroad that every Irishman would gladly board to get away from the tyranny of England?” Douglass must answer judiciously as his words will resound back to his sponsors in Britain and America.

“What is to be thought of a nation boasting of its liberty,” he says, “yet having its people in shackles? It is etched into the book of fate that freedom shall be universally delivered. The cause of humanity is one the world over.”

Unfortunately, I can only hint in this space at Colum McCann's achievement in bringing Frederick Douglass's Irish odyssey to life. It is all there: his brief descent into the staggering filth and degradation of Dublin's underclass (“Douglass had never seen anything like it, even in Boston...Men lay collapsed by the railings of rooming houses. Women walked in rags, less than rags: as rags.”); his near-supernatural journey by horse and carriage through a hunger-ravaged land (“In the road they saw the cold and grainy shape of a woman...dragging behind her a very small bundle of twigs attached to a strap around her shoulders...On the twigs lay a parcel of white. 'You'll help my child, sir?' she said.”).

More humorously, his exceedingly moist introduction to Irish weather (“Rain fell more steadily now. Grey and unrelenting. Nobody seemed to notice. Rain on the puddles. Rain on the high brickwork. Rain on the slate roofs. Rain on the rain itself.”).

So as a fitting observance of Black History Month, pick up a copy of TransAtlantic and introduce yourself to Frederick Douglass, freeman and adopted son of Eire.

*Boston native Steve Coronella has lived in Ireland since 1992. He is the author of Designing Dev, a comic novel about an Irish-American lad from Boston who's recruited to run for the Irish presidency. His latest book is the essay collection Entering Medford – And Other Destinations.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments