How one Irish man is continuing six generations' worth of traditional tweed at Molly & Sons

*Editor's Note: This article was originally published in 2014.

When Kieran Molloy, 28, lost his job as an industrial engineer to the recession, he found himself back at home in the little village of Ardara (pop. 731), in southwest Donegal.

There are worse places to fetch up. In 2012, it was voted the best village to live in Ireland by The Irish Times. You can see why: the locals are friendly and the dramatic setting, on the side of a sloping hill that leads down to the wild Atlantic coastline, stops the heart with its natural beauty.

It was while kicking around at home wondering what to do next that Kieran suddenly realized that the future was looking him in the face. For six generations his family has been in the Donegal textile business, ever since his great-grandfather Edward Molloy began weaving in the 19th century.

Kieran decided he would follow in his footsteps. He would put his NCAD (National College of Art and Design in Dublin) training to good use. He would make things instead of just drawing them.

“I was knocking around at home for a while and I’d always been interested in the weaving,” Kieran tells IrishCentral. “I always worked summer jobs here growing up. The work sheds are twenty feet from our house. I’ve always been interested in it.

“While I was hanging around at home my dad (Shaun) and I decided we may as well do something. So we set up the weaving as a separate company from my granddad’s original knitwear company. It's a new father and son enterprise. We’ve been doing that for three years now full time.”

It was a significant decision that paid off quickly. What makes Donegal tweed special, what makes it sought after internationally, is its unique color, beauty, and quality. The process of making it is unlike any other, resulting in a signature color-flecked weave. But in recent decades, due to long-term government neglect of the industry and poorly targeted international promotion, the once flourishing industry has dwindled to less than a hundred makers countywide now.

“I’m the sixth generation doing the same thing in the same spot,” Kieran explains, underlining how long and how well his family has represented their village, county.

“A lot of what we’re doing is heavily based on what’s come before, what’s in our archives, but we’re changing things now like our color combinations, and what the base colors are to reflect the countryside and nature around us here in Donegal,” Kieran explains.

Inspired by the dramatic ever-changing beauty of the ocean, the changeable sky, and the flora and fauna of the nearby hills and mountains, the tweed produced by Molloy & Sons tell the story of the village and the county through the colors and tones found in their tweeds.

“We also focus on more contemporary designs that our customers ask us for. If we’re asked for a navy with pink and blue and yellow spots in it we will do that. We are not doing anything super complicated, but we are making subtle changes every year with texture or trying to be a bit more geometric. We don’t do so many checks, we do more basic patterns but try to change it up with the colors or the textures.”

Within months of setting up their business the quality of the work they were producing was so good it could be seen from as far away as Tokyo. A buyer from Beams, one of Japan's foremost menswear labels, saw the opportunity to partner with the Donegal-based company, to offer their customers something special.

“We hadn’t sold to people in Japan before and so they saw the opportunity to develop something special for themselves, which would also be a unique selling point for themselves. So they came over from Tokyo and bought stuff and we have been working with them since.”

Japanese tailoring, with its legendary attention to detail, and superior Donegal fabric made for an exhilarating match. The blazers that resulted from the partnership flew off the shelves. It's proof of how times have changed. Kieran's grandfather had to travel to Japan in the 1960s to drum up business, but the internet age has changed all that.

“A lot of our promotion isn’t about us pushing our work out there. It’s more from people around the world finding out about us and then getting in touch. We’re not chasing down fashion bloggers to write about us. The internet has changed the way the business is run.”

Molly & Sons finds its main customer base via the internet and through admiring write-ups on international style blogs. It's a two-way exchange, Kieran says: “You find out through the bloggers what’s happening in the world and you stay in touch that way, even though you’re on the side of a hill in Donegal.”

Kieran explains that his grandfather John used to visit Japan in the 1960s selling the Donegal tweed and knitwear designed by his company, but it was challenging work at the best of times. “For him, it was all about knocking on doors after writing letters months beforehand,” Kieran explains.

“At the time you could only find the main companies in the market there, it was harder to find the smaller niche suppliers. Now on the internet, you can contact massive corporations all the way down to individual designers running their own one man or woman shows and you can deal with all of them one-on-one. Even if they’re located on the other side of the world. When grandad was doing it, it was a difficult proposition to get new customers in Japan or Korea. You can do it without any difficulty now."

When Molly & Sons have recently featured on the LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy, the world leader in luxury and prestigious brands) website Nowness, it introduced the father and son Donegal company to the world's top creative directors and fashion leaders. Interest was immediate. Top fliers from the world of fashion found themselves flying over to visit the modest little village and the staggeringly beautiful county in which it's set.

So after a promising start, Molloy & Sons are now succeeding in the same way that other innovative and savvy Irish designers like Inis Meain are, by becoming part of a quiet revolution in quality, look and fit and taking their work to high-end markets worldwide where the quality is immediately recognized.

Revolution is not too strong a word for what's happening in Irish design. For decades Irish fabric and knitwear were defined by the boxy, baggy horrors that were made one size to fit all. That era is over. “It’s the design part that was never invested in,” Kieran explains. “It’s how the industry originally evolved. You made a big sweater that would fit lots of people of all shapes and sizes. That widened the audience but also limited its appeal.”

Back in the late 1960s when the Irish government was setting up the famous Kilkenny design workshops they invited a group of accomplished Scandinavian designers to come over and write a report about the state of Irish design and manufacturing.

What does Ireland produce that we should focus on, the government asked them? The visiting designers toured the country and replied that the government should invest more in education about design; and of all the industries, which included pottery, glass, and knitwear, they said Donegal Tweed was the most valuable facet of the Irish design industry. Protect it, they said. They even suggested the government set up a museum to teach its history.

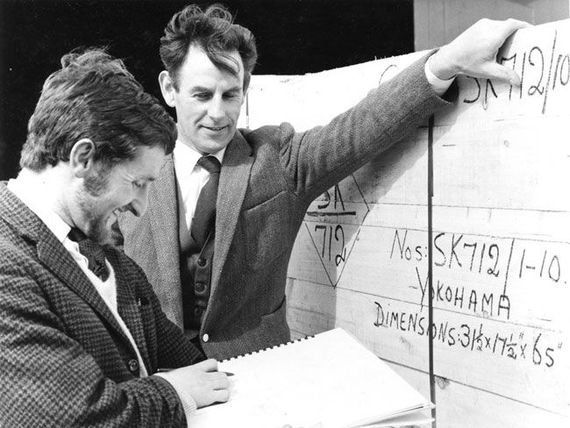

Kieran's grandfather John Molly pictured at his factory in the 1960's.

But their suggestions were ignored. The 1970s and a brave new world of polyester and ready-to-wear garments were dawning, and so the government determined Donegal Tweed was a dying industry.

Within twenty years of the Scandinavian report, the whole industry of Donegal Tweed as it once was had collapsed. Told that they were sitting on a gold mine, the government of the day decided the thing to do was to shutter it.

That brings us back to 2014 and Molloy & Sons. Anxious economic times or perhaps a fatigue with ready-to-wear have seen international menswear designers rediscover their enthusiasm for exceptionally well made and tailored menswear. In a time of austerity, it seems luxury is back in fashion.

Liz Hershfield, Vice President of Sourcing and Production at Bonobos, the top tier menswear company, told IrishCentral: “The trend really has been getting back to heritage fabrics, a mix of old and new. We started working with Donegal fabrics last year, it was our first season working with it. Our customers respond well to authenticity. They like hearing where the fabric comes from and all of these suppliers are hundreds of years old and they have a rich heritage that really helps us tell great stories about the product.”

John Molloy

Molloy & Sons represents everything that their customer base reveres, Hershfield says. “Molly & Sons being a sixth-generation mill is the kind of opportunity our designers and tailors get super excited about. They know they’ll be working with people who know what they’re talking about, they know the quality will be great, so it makes their job easier and it allows them to get really inspired. It also allows them to mix what is trending in tailoring with the heritage fabric. The casual Friday look is going away a little bit and men are dressing up more these days.”

Ninety percent of what Molloy & Sons is currently selling is menswear. Ninety-five percent of it is made for export, Kieran explains. But they have ambitious plans for the new year. “There’s a huge woman’s market out there that we haven’t gotten into yet. It would mean brighter fabrics and bolder patterns,” says Kieran. “We will slowly try to creep into that market more in the year ahead.”

The 28-year-old is the latest in a long line. Although Molloy & Sons were started three years ago by Kieran and his father Shaun (who's in his 50s) it has evolved from his grandfather's company, which started in the late 1950s. Before that, his grandfather had worked alongside his own father as a sole trader. And his father worked with his uncle (Kieran's great-granduncle) who had a weaving company from 1910 with a showroom and warehouse in New York City in the 1920s. That warehouse was located in the meatpacking district, about two blocks from what is now the Standard Hotel, the showroom was on the 5th avenue corner of 40th Street.

Kieran's great-grandfather worked with his brother and spent a lot of time in America. Their father before them was also a weaver. So the list goes Edward, James, Michael, John, Shaun, Kieran. There's magic in a line that long and in the enduring strands that it still weaves. They represent everything we should cherish about our own history and our eye for beauty.

You can learn more about Molloy & Sons on their website.

Read more

*Originally published in 2014, updated in September 2020.

Do you own any Irish Tweed? Let us know in the comments!

Comments