Quick! Without cheating – stay away from the Internet – name the four Irish Nobel Laureates in Literature. Got them yet?

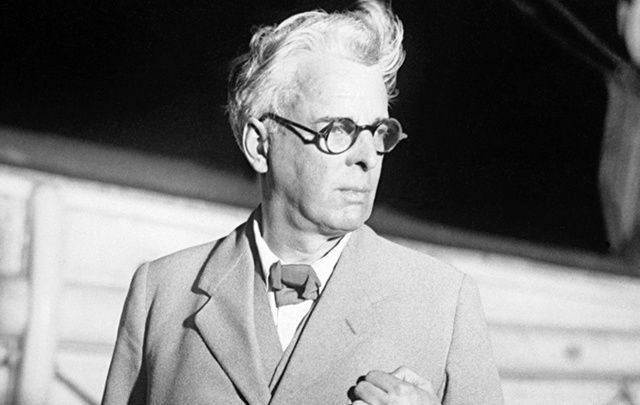

OK, Yeats, the first, is the easiest.

Beckett, the most popular.

Heaney, the last, is often forgotten.

Who’s missing?

Usually, people forget George Bernard Shaw, who some think English, although he was born on Synge Street in Dublin, not far from the Grand Canal.

If Ireland is known for anything, it is probably the disproportionate number of world-class writers it has produced compared to its small population. Four Irishmen have won the Nobel Prize in Literature: William Butler Yeats (1923), George Bernard Shaw (1925), Samuel Beckett (1969), and Séamus Heaney (1995). All of them, except Heaney, are Protestant. And, in their own way, many of these exceptional writers have fought for Ireland.

Read more

The Archpoet makes his mark on Ireland

I doubt that any one country had a poet who contributed so much to culture, revolution, and change as William Butler Yeats.

Yeats’s play "Cathleen Ni Houlihan" premiered on the opening night of the Abbey Theatre in 1904. The play takes place during the Rising of 1798 and the heroine of the title represents the Irish nation. It is fiercely nationalistic and encourages armed rebellion. Years later Yeats would write: “Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot?” After the 1916 Easter Rising he would immortalize the events and the players in such poems as “Easter 1916,” “Sixteen Dead Men,” “The Rose Tree,” and “The Ghost of Roger Casement.”

We tend to see Yeats as this solemn, reflective character, but when he was notified on the telephone by the Irish Times that he had won the Nobel Prize, his reaction was typical of any writer with financial problems: “How much is it? How much?” After winning the Nobel, Yeats would serve his new country as a Senator.

Yeats recites “The Lake Isle of Innisfree”:

Shaw confronts the English

George Bernard Shaw is often thought of as a British playwright. In fact, when Samuel Beckett won the Nobel, the august New York Times reported that “The only Irish Nobel winner in literature was William Butler Yeats, the poet, in 1923. George Bernard Saw, born in Ireland, was honored a few years later but as a British author.” The Times, in continuing their anti-Irish bias, went on to say, “It was not immediately clear whether Mr. Beckett should be regarded as an Irish or a French winner…” As usual, when it came to the Irish, the newspaper of record got it wrong – again!

Shaw was a tough nationalist in his own right. As the British were preparing to hang the last rebel of the 1916 Rebellion, Sir Roger Casement, Shaw fought to save him, but to no avail. The British would have their sixteenth martyr. He later became a friend of fiery revolutionary Michael Collins and would dine with him on the last weekend of Collins’s life. After his death Shaw would exuberantly write to Collins’s sister: “I rejoice in his memory, and will not be so disloyal to it as to snivel over his valiant death. So tear up your mourning and hang up your brightest colours in his honour; and let us all praise God that he did not die in a snuffy bed of a trumpery cough, weakened by age, and saddened by the disappointments that would have attended his work had he lived.”

Shaw also shares a unique place in the annals of Irish letters. He is the only person to win the Nobel Prize and an Academy Award, for writing the screenplay for "Pygmalion" in 1938.

Shaw on the filming of Pygmalion:

Samuel Beckett: Minister for Justice

Beckett was born in the determined Anglo-Irish Dublin suburb of Foxrock. He was Irish to his core. In fact, when a foreign journalist who was interviewing him asked, “Mister Beckett, you are British?” he swiftly replied, “Au contraire!” After fighting in the French Resistance for four years during World War II he went home to Ireland, joined the Irish Red Cross, and swiftly returned to France. Upon hearing the news of winning the Nobel he lamented, “Alas no Irish [whiskey] here—only Vat 69, or still lousier Donats.”

There is a burning desire for justice in Beckett’s work. In his novel, "Mercier and Camier" he recalls Noel Lemass, brother of the future Taoiseach, who was brutally murdered by agents of the Free State government in 1923. Beckett wrote about lonely Glencree peak where Lemass’ body was discovered:

“It was the grave of a nationalist, brought here in the night by the enemy and executed, or perhaps only the corpse brought here, to be dumped. He was buried long after, with a minimum of formality. His name was Masse, perhaps Massey. No great store was set by him now, in patriotic circles. It was true he had done little for the cause. But he still had this monument. All that, and no doubt much more. Mercier and perhaps Camier had once known, and all forgotten.”

Before fighting fascists as a member of the Resistance, Beckett took a dim view of Generalissimo Franco’s fascistic antics in Spain. In 1937 he signed a petition against Franco which was entitled: “Writers and Poets of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales: Are you for or against the legal Government and the People of Republican Spain?” The writers who signed were asked for their rationale in signing and also asked not to exceed six lines. Beckett’s answer was pure Beckett and pure Irish: “UPTHEREPUBLIC.”

Samuel Beckett reads from Watt:

Heaney remembers the Croppies

Séamus Heaney was born in County Derry in 1939. When he won the Nobel, the committee said his poems were “works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past.”

When asked how it felt to join the ranks of Yeats, Shaw and Beckett, Heaney modestly replied: “It’s like being a little foothill at the bottom of a mountain range. You hope you just live up to it. It’s extraordinary.”

In 1966, before the Troubles and on the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, he wrote the heartbreaking “Requiem for the Croppies,” which recalls the ghostly rebels of 1798—the “Croppies” because of their short, cropped hair—who bravely fought and died:

The pockets of our great coat full of barley…

No kitchens on the run, no striking camp…

We moved quick and sudden in our own country.

The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp.

A people hardly marching…on the hike…

We found new tactics happening each day:

We’d cut through reins and rider with the pike

And stampede cattle into infantry,

Then retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown.

Until…on Vinegar Hill…the final conclave.

Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon.

The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.

They buried us without shroud or coffin

And in August…the barley grew up out of our grave.

Tommy Makem Recites “Requiem for the Croppies”:

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of the "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," now available in paperback from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at dermotmcevoy50@gmail.com. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook at www.facebook.com/13thApostleMcEvoy.

*Originally published in 2017. Updated in September 2022.

Comments